A handful of shops on Maipú Street concentrate the old but still current passion for stamps. A world that combines the drive for collecting and an erudition made of places, names, dates and filigrees.

When he was very young, Alejandro Argüello was the shadow of the postman from his neighborhood. The courier delivered the envelopes on time and, a few seconds later, the philatelist’s pigeon rang the bell and asked the recipients to give him the precious stamps. “I was eight years old, few economic resources and in my family no one collected – explains the current president of the Society of Philatelic Merchants of the Argentine Republic – but I could not complain, the neighbors of Florida were always very generous.” Of those initial postal treasures, he could never forget the 4-peso stamp tattooed with the face of José Hernández: the red sealing portrait of the gaucho poet, the fine vignette and the precise teeth. “I took it out of an envelope in a handmade way, I didn’t have the faintest idea how to do it. This is how I came to this world. The thing was instinctive ”. Before turning 15, Argüello already had a generous –but messy– lot, populated by Argentine and French pieces. “One day my old man, who was an employee of the French Bank, fell home with a bag full of 5000 letters, archived correspondence and then released by the bank. I felt the same as when Santa Claus came ”. In full adolescence, somewhat fed up with vice, he decided to sell everything. He took a bus to Plaza Dorrego and decided to enter a small place where he was attended by an old and wise collector: “That day I understood the meaning of philately. He explained to me that what he had was not a collection and he revealed to me how to put one together ”. He returned home with the stamps, but also with a classifier and a clamp, the two fundamental weapons of every legal philatelist. Since then, he has not spent a single day without ordering the postal universe that surrounds him.

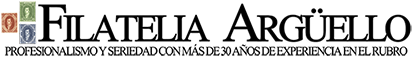

Silvia Kevorkian, Argüello’s wife, learned to play with stamps rather than dolls. The philatelic drive is attached to her family history: grandfather, father, all Kevorkians loved stamps, “until at one point my brothers were opened. So I am the only one who followed the tradition with the place on the street –said the lady, hand clamps, in her small and famous shop in the Microcentro–. I am not a collector, what I am passionate about is commerce, encouraging clients, giving them conservation guidelines, but above all learning from them. Philatelists are very cultured people, they know everything. My husband has the memory of an elephant ”. Among the many scholars who visited her domain, Kevorkian does not hesitate for a second and chooses “Mr. Antonio Carrizo. She collected everything that had to do with literature, Borges was her favorite. But his maximum passion was Boca Juniors. Here he bought a letter from 1910 with the seal of the Boca Secretariat, addressed to a player from the Alumni club. A jewel”.

In the 1980s, Argüello and Kevorkian had stalls at the fair that surrounds the long-lived ombú of Rivadavia Park, the historic mecca – not forgetting the El Coleccionista bar – where the faithful of Buenos Aires make religious pilgrimages every Sunday. For decades they have premises in the galleries of Maipú at 400, in what remains of the capital’s philatelic pole. They were not joined by any love letter. It was the meetings in the merchants’ society that certified their flirtations. They hit a wave and soon stuck like stamps. The couple collects thousands of pieces in their stores, but they confess that they could not choose their favorite. “I don’t have a fetish,” says Argüello and reviews the latest national releases, with images of Mafalda and Sandro. Or rather, our fetish is to have that stamp that we once saw and never had ”.

Letter to an english lady

The strange advertisement appeared in print in the pages of the London newspaper The Times in 1841. A young woman was looking for the original “black pennies” – the first adhesive postage stamps, printed a year earlier by the British Post – to “wallpaper her dressing table with used stamps” . From that seed, her passion for stamp collecting was born. On August 21, 1856, the first Argentine stamp appeared in the province of Corrientes. “Here the series starts with the famous‘ escuditos ’- dictated by the Argüello chair -, which were very easy to forge. Then came the Rivadavia, who were made by the English. The first commemorative stamp in the world was made in our country, it came out in 1892 and it remembered the ‘discovery’ of America ”.

For Argüello, the golden age of philately occurred at the beginning of the 20th century. Argentina, he maintains, was a power in the niche. Imagine that the famous Stanley Gibbons house chose Buenos Aires to open its first location outside of England. It was just here, near the Central Bank. But it closed in the midst of the crisis of ’30 ”. Despite the economic booms and cracks and the considerable technological changes that changed the activity, philately continues. “The stamps, beyond their commercial purpose, tell the story of a country. I assure you that many people would not know what the faces of Güemes or Alberdi were like if it weren’t for the stamps ”.

Rescue yourself!

Carlos Alberto Chiavello has been a collector for as long as he can remember. Badges, cigarette labels and wine labels, snails and stamps, especially stamps. “The one who collects has those habits. I have everything, but my strength is postal history ”, he is sincere as he catalogs a stack of distinguished postcards printed for the centenary of the May Revolution. “He is stronger than me, I buy everything I can. I started with my father in a stand with an umbrella in Rivadavia Park. We had two little suitcases full of letters. Today I have the premises, the basement and an office up here full. I think I would need a container to store everything, ”says the collector, 51 years old, besieged by piles and piles of boxes of which he claims to have a meticulous inventory in his memory.

Chiavello is an eminence in postal history, what he calls “the superior branch of philately.” “It is an evolution. There are many fundamental details that are lost when the stamp is removed from the envelope: how it was transported, who did it, if there was censorship. The letter is a historical testimony ”. He specializes in correspondence from the Spanish Civil War and the two World Wars. His work is that of the historian who sheds light on the past. Of the thousands of pieces that he rescued from oblivion, he remembers a letter written in German by a Polish worker during the Nazi regime. “It was one of the first that I had translated. The woman recounted how they were transferred, how they lived crowded together in smaller and smaller places. It is very strong. My intention is to rescue these letters, which are part of people’s lives, because I don’t want them to be lost forever ”. In the family establishment, his young son Lucas, to whom he could not pass on the epistolary legacy, gives him a hand: “I tried everything: stamps, old coins… but the new generations are immune. The culture of shooting reigns ”.

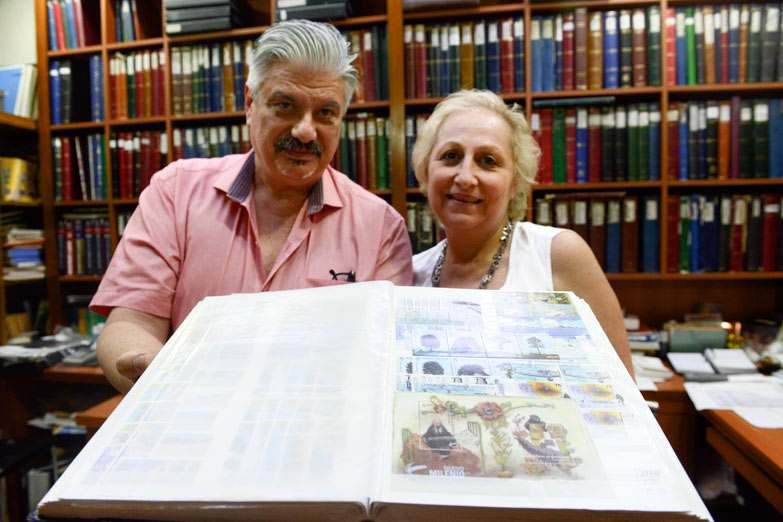

Before being portrayed in the crowded basement, the collector takes from a shoe box a letter stamped with air stamps and a handwritten signature: “This little piece is beautiful. Year 1929, first flight between Comodoro Rivadavia and Bahía Blanca, carried out by Aeroposta Argentina, a subsidiary of the French. Look at the pilot’s signature –Chiavello strokes the paper and brings a magnifying glass to the rubric–. Yes, sir: Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the author of The Little Prince. He sees why the magnifying glass is fundamental for the philatelist ”. Most of the time, the essential is invisible to the eye. «

Source: Tiempo Argentino